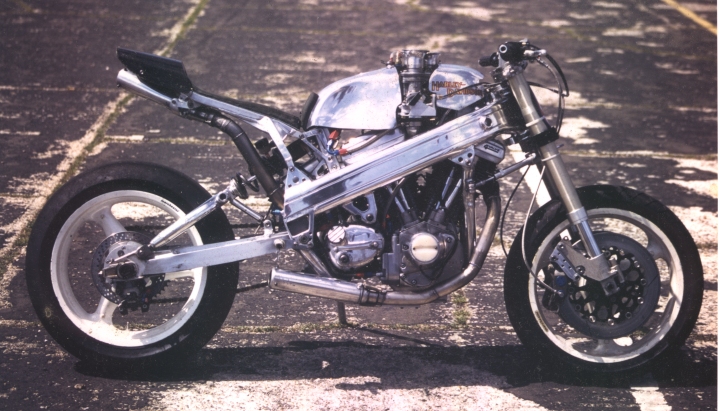

My Harley Race-bike

I would like to dedicate this page to my mate Alan Welsh who tragically died at his welding bench

Without his assistance, this build would not have been possible.

Spec sheet - Tech Stuff

Owner:.......................Patrick Hook a.k.a. "Paddy" (heavily modified!)

Fabrication by:...........Owner / Welbro Engineering

Chrome/Paint:............None - weighs too much

ENGINE

Builder:......................Owner

Size/Type:.................1232cc, short stroke, 4-valve, (was an Evo Big Twin)

Cases:........................Delkron, modified

Crank:.......................One-off S & S flywheels, modified and balanced by owner

Rods:.........................S & S Supreme Duty, bored out to take Cosworth pins

Pistons:.....................Cosworth 90mm Formula One race car, heavily modified

Cylinders:.................Stock, shortened, bored out, Beryllium Rings (no head gaskets)

Cam:.........................Fueling 4-valve

Carbs:.......................2 x Weber IDF 40mm twin-throat racing, intakes by owner/Alan

Heads:......................4-valve Fueling, modified

Ignition:....................Interspan racing system, no external power supply needed

Air Cleaners:............Pancake-type

Exhausts: .................Titanium, computer calculated length, matched front and rear

Silencers: .................It'll make your ears bleed!

TRANSMISSION

Type:..........................Four speed wide-ratio

Manufacturer:............Quaife Racing

Clutch/Primary:.........Bob Newby Racing belt, alloy clutch and front pulley

CHASSIS

Year/Type:..............1994, Owner/Welbro Engineering, 7020 Aluminium twin beam

Swing Arm:............Suzuki 1100, heavily modified.

Forks:......................Kayaba Upside Down Grand Prix

Rear shock:.............Kayaba Grand Prix, Titanium spring

Fasteners:................Titanium, through drilled, safety wired

Overall weight.........325 lb.!

WHEELS/TIRES

Wheels:................Marchesini Magnesium Grand Prix

Brakes:.................AP Racing Grand Prix Calipers/ Carbon Fibre or Steel Rotors

Tyres:...................Michelin Grand Prix, Wets, Intermediates or slicks

Size:.....................130/17 inch front, 180/17 inch rear

No Compromise - The Spirit of Semtex (October 1994)

My life-long obsession with racing began at the tender age of seventeen, when I saw my first hillclimb. Up to a mile of madness, on some of the craziest bikes you could imagine. I couldn't wait to start competing, and first started by using modified road machinery, but soon built my first out-and-out racer, a 750 Norton I called 'Dingbat'.

I was, however, a long term fan of dirt track XR750's - so I wanted a Harley. My secret fantasies were of a 300lb bike, with a big motor and mega horsepower. I knew that in drag racing Big-Twins were extremely fast, so I looked a bit closer. They obviously had a lot of potential, and the cost wasn't bad when compared with most racing engines.

And so my fantasy began to take shape. I started out building it in my kitchen, and used the motor from my road bike, an Evo 1340. I then gradually constructed a killer race engine - a short-stroker with light flywheels, and high rpm. As the class limit is 1300cc, I had to lower the capacity - at the moment it measures 1232cc, but will soon grow to 1290cc. I made the frame from seamless steel tube, and finished it in time to compete in 1988. I raced a lot, riding hard and crashing often - a painful, but effective development process.

At this time I had been working in racing car engine development, and had made full use of the facilities to hand - there are lots of nice bits used in Formula One cars! I had been specialising in computers, which led to me working with on-board data-acquisition. In 1991 I put a Formula One system on a bike - Terry Rymer's Loctite Yamaha, which was the first time it had been done with this level of equipment. Soon afterwards I got poached by Lucky Strike Suzuki, to engineer for Kevin Schwantz, Doug Chandler, Alex Barros etc.

This meant access to a whole lot of components that I wouldn't normally ever get near. I made sure that I made myself useful to lots of people. For instance, I wrote a lots of software for Kayaba to assist with their active-ride suspension project. A bit later they made available a pair of Schwantz's forks, and a rear shock. Likewise I did Michelin a wheelspin analysis programme, and got some racing tyres. I carried on like this for three years, amassing enough parts to start a new version of the bike.

After I left Suzuki I had more time, so I got together with Alan Welsh of Welbro Engineering to build the new bike. He's one of the best alloy welders around (and also a bloody good engineer). Locked away in deepest Devon, he lives like a hermit, working all hours, seven days a week.

I succeeded in driving Al completely mad - my philosophy is NO COMPROMISE, anywhere, anytime. The bike had to weigh nothing, be as small as possible, look lovely, and be technically wonderful.

We decided to make the frame from some 7020 aluminium extrusions he'd had made for a batch of chassis kits. It's an aerospace material with good resistance to cracking, which welds nicely, but doesn't require heat treatment. It's triple box in section, and complete overkill, but about right for an over-the-top Harley.

When I was with Lucky Strike Suzuki, I wrote and developed a chassis geometry analysis programme, so using this knowledge I drew a full layout, including all the relevant co-ordinates (swing arm pivot position, steering head location, etc.). We were then able to set the frame jig to the angles I wanted, along with the motor, transmission, swing arm etc.

I wanted to reduce the polar moment of inertia - this is perhaps best explained by imagining a weight lifting bar, with a heavy disc at each end. If you pick the bar up and try to turn around, you'll find it's hard to move. Once it's moving though, it's even harder to stop. If you now move the discs to the middle, you can turn easily. It weighs the same, it's just that the mass is now concentrated. A motorcycle is no different - if you try to hustle through a fast set of corners, it'll steer much faster if the heavy bits are near the centre.

So to achieve this, I moved the clutch and gearbox forward by three inches - something I couldn't do before as there was a bloody great frame tube in the way. I was then able to add the extra length into the swing arm, without changing the wheelbase. It allowed me to optimise the rear geometry as well, something I'd wanted to do for ages.

I also wanted to move the mass centre up. This sounds controversial, as most people try to get the weight down, but the bike becomes too stable. Lovely in long sweeping corners, but it'll stuff you right up in 'S' bends. By raising it, there are forces trying to lean the bike the other way, so changing direction becomes much faster.

The main reason that I chose a beam frame, was that by having no rails above the motor I was able to exploit its full potential. Originally, as I'm sure you're well aware, Harleys have a single carb sticking out of the right hand side. This means they've got just about the worst manifold efficiency of anything this side of a golf-cart. Not only does this restrict gasflow, but you can't fuel each cylinder independently, which is a must for max horsepower.

When I got my Fueling four-valve heads, I was impressed by several things - the quality of the forged rocker arms, the combustion chamber layout, the valve geometry etc. They had all the right features for a real racing engine. I was also able to build a radical intake system - two vertical twin-throat Weber IDF carbs (one per cylinder) leading into fully downdraught manifolds, (one per valve) to make best use of the intake port angles.

This may seem a bit obscure, but the reason that current bikes make so much power is due to downdraught head design. Take a look at any proper racing engine (like a Formula One car). The gas flow has a better approach angle, so a greater percentage of the valve circumference gets used - effectively it's free horsepower.

This was all very well, but making the manifolds drove both Al and I to near complete psychiatric failure. Because I had short-stroked the motor, the heads are very close together. This left almost no space for the manifold risers, which also had to clear the frame spars, and still leave room to fit the carburettors. We must have re-made the bloody things about fifteen times before they fitted. The finished parts are a testament to Al's ability with a TIG torch, curving and twisting like tree trunks from some primeval forest.

Every component was examined to see if it could be made lighter. Could I put a chamfer or counterbore anywhere? Could I drill any holes or reduce wall thicknesses? If it was too heavy it got thrown away, and a replacement was made out of titanium, magnesium, or carbon fibre. Yet again, NO COMPROMISE would be allowed. Mind you, if I drove Al mad over weight, he got his own back. Before he would weld anything, it had to be mirror polished. That meant hours of standing in front of a huge spindle mop, getting black from head to foot with cutting compound. Then he'd say we'd done a crap job, and go and do it all himself.

One of the most impressive jobs Al did was to make the gas tank. The whole upper half is made out of a single formed aluminium sheet. He's still not happy with it though, because if you stand in a certain light the weld is a slightly different colour. Is he the ultimate perfectionist? Whilst we were at it I finally got to make my titanium pipes. I'd obtained some offcuts from the Suzuki race shop in Hamamatsu, and had been waiting to use them for two years.

What's the bike like now? Well the steering response is great, and the motor goes like hell. I still can't get enough weight over the front to stop it spitting me off though. As I write this I have two broken toes, my right leg is broken above the knee - having stuck the bone out of the side, it's also broken at the hip (and held together with an internal titanium bar and four bolts), all four fingers on the right hand were dislocated at the wrist - which also got broken, and I have injuries to my thumb, shoulder, neck, chest and head. How? well, it highsided me straight into a trackside gatepost at high speed.

Without putting the bike on a dyno, it's very difficult to quantify its performance, but to get some idea of scale, we put the specs into one of the top engine analysis computers in America, and got numbers in the region of 135bhp. Couple this to a weight of 310lbs, and you've got one and a half times the power to weight ratio of a Fireblade!

So yes, the bike is smashed up right now, and I've got yet another winter of rebuilding myself, and then the bike (just like last year, when I trashed most of my right shoulder). Why do I do it? Who knows, maybe I'm trying to get more titanium parts than my bike. Will I be racing it again this year? Of course, but if you want to see it in action you'd better get there early - I rarely last the day without getting wiped out. Hence its name, Spirit of Semtex - every inch of the way it's trying to kill you!

2009 Update

A photo taken at the 40th Anniversary of the first all-bike event at Wiscombe Park Hillclimb

2023 Update

After more years than I care to admit to, I decided to put the bike back on the track in 2019 - more specifically, on the sprint/drag strips. To this end, I added eight inches to the wheelbase, fitted a magnesium six-speed Quaife gearbox, and made a whole host of other mods/improvements.

There is a link to a video of the bike's first start-up in 25 years on the homepage!